(This post originated just prior to Christmas 2009. It still seems relevant, so I’m reposting.)

In my prayer time the other day I was pondering Psalm 43:3, “O send out your light and your truth; let them lead me; let them bring me to your holy hill and to your dwelling.”

Truth and good order go together. The shalom of God means that truth and good order lead to human flourishing. God’s created order means goodness and blessing for all. Implication: truth cannot be a secondary matter.

Talking about truth sounds to many people like a mere intellectual game. The spirit of the age encourages people to separate the experience of God’s goodness from doctrines about God’s nature and work. Some people argue that one can have a powerful and life-changing experience of God without being committed to (or even very worried about) truth.

Clearly, we don’t have to be perfectly logical and coherent in order to experience God’s goodness. Certainly, there are flaws in my concepts of God and I still experience God’s goodness. But I don’t think this point gets at my concern about the spirit of the age. The problem is that we almost entirely divorce truth claims from experiencing God’s goodness, as if we can have heads full of seriously bad ideas and still experience the fullness of God.

We mostly soft-pedal doctrinal differences. We don’t like doctrinal debates (too abstract and probably irrelevant) and we don’t like to tell people openly, “You’re wrong,” even though we think it all the time. The underlying assumption seems to be that doctrine really doesn’t matter very much – that God is so gracious and good that God apparently overrides really bad ideas with grace and love anyway. But, of course, I just made a doctrinal (or theological) claim about God’s goodness.

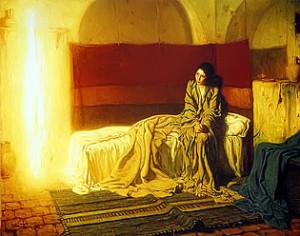

Does God care whether I think A or B about God? Since we’re approaching Christmas, is it truly only of secondary importance that some Christians dismiss a literal incarnation of the Word of God, preferring to think of it as metaphorical and not actual? Does thinking A rather than B have no impact on their spiritual lives? Their experience of God? Can we grow to maturity either way?

If there is no real life from God in true doctrine, then about any old idea works. If doctrine is nothing more than manipulating concepts, while experience of God lies elsewhere, then any old idea works, because God apparently works independently of ideas. But of course, not any old idea works. If any old idea worked, then God-as-cruel-Tyrant works as well for helping me flourish as does God-as-loving-Parent.

Having a head full of the right ideas that don’t penetrate one’s heart is not what the Christian life is about. Neither is the opposite, that one need be unconcerned about sound doctrine because God will bring a flourishing life anyway.

I believe that those people who are captivated by the incarnation of the Word of God will have a dramatically different Christmas experience than those who think it’s just the birthday of Jesus. There. I said it.