A blessed Christmastide to you and Happy New Year. This time of year always brings on a taking stock frame of mind. Recently mine has revolved around pondering the dual aspect of reality – seen and unseen. How does the seen give a glimpse of the unseen?

In Isaiah 6 we encounter the well-known vision of the prophet, who sees “the Lord sitting on a throne, high and lofty; and the hem of his robe filled the temple.” And seraphs sing “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory.”

“The whole earth is full of his glory,” a glory unseen, at that moment, except by the heavenly court and Isaiah. The first five chapters of Isaiah show the other side of reality – the seen, the usual, the normal. As we read, we get the impression of life very much like what we in our time have come to expect. People are busy, working hard, gaining, losing, grasping, chasing the dream and terrified of being left out. They work hard and they play hard. The rich get richer and the poor get poorer. And, oh, yes, there is the 2020 version of the plague. And too many of God’s people carry on as if God isn’t present or concerned about the way things are going. We’re fixated on the seen and forget that the unseen is real and present.

And then comes Isaiah’s vision and precisely here the seen Unseen gets interesting. I can read it as just that, Isaiah’s vision. We can describe it by how certain psychological factors may have produced this vision (assuming it to be an actual experience and not merely a literary construction). We might read a neurological study. We might dip into anthropological theories. We could go on and on imagining and analyzing, using the best scholarly tools available to understand Isaiah’s experience. We might, then, better understand human experience in general and be able better to make sense of ours.

Isaiah says, however, that he saw the Lord. The Lord is the Holy One of Israel, the Creator of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible. Isaiah shows repeatedly that the Lord spoke to him and through him to the Lord’s people, about real-life circumstances and the attitudes and actions of real-life people. While we’re focusing on Isaiah’s mystical experience, Isaiah is focused on the one true God. The Unseen appears, if only for a moment. And Isaiah tells us about it. He shows us. Do we have eyes to see?

Our temptation is to be satisfied with understanding Isaiah 6 through familiar, but strictly human categories. In Charles Taylor’s masterful study, A Secular Age, he names this tendency the “immanent frame.” We have been schooled, literally, to think only in empiricist terms and that schooling has become so deeply embedded that we don’t recognize it as a problem. We have so habituated ourselves to the seen, to what we call “the real world,” that modern society now has a massive, self-imposed blind spot.

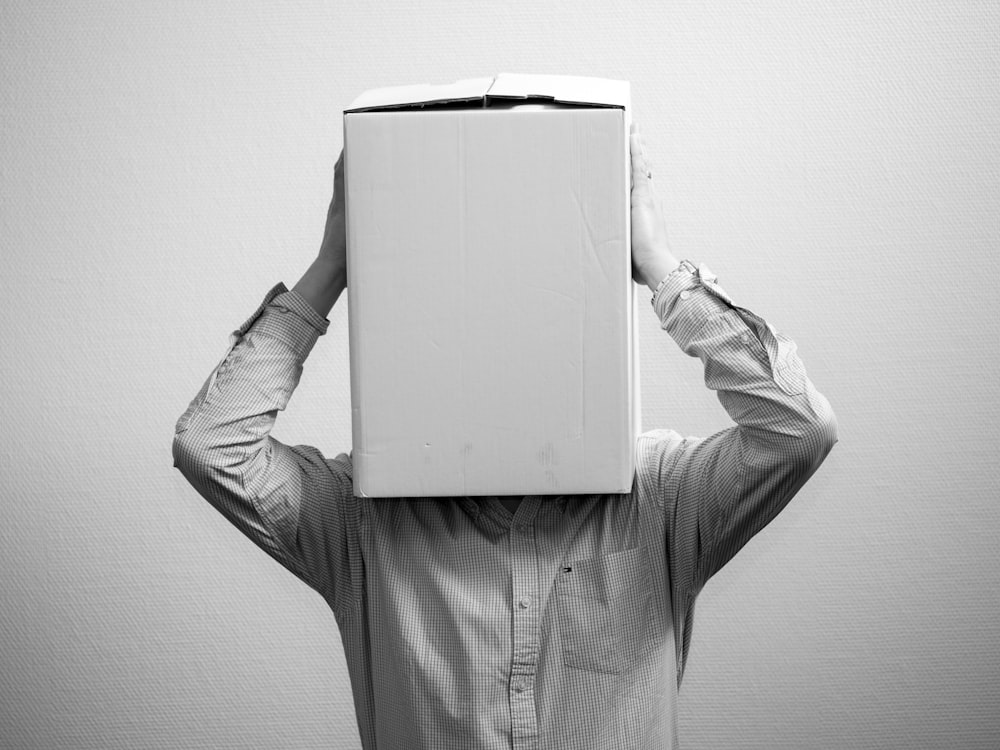

My general psychology class in college was typical for the time: a large, austere lecture hall with hundreds of students. We read B.F. Skinner’s Walden Two and I don’t remember what else. Fortunately, the professor was a very engaging lecturer, with just enough quirkiness to keep us interested. For example, for two weeks, if I recall correctly, he wore a device that sat on his head, like eyeglasses, with two tiny slivers of metal, like pendants, hanging down in front of his eyes. The contraption somehow responded to his eye movements so that those little metal slivers stayed in the center of his vision, no matter which way he looked. When he went outside, he put a box over his head, with the smallest of slits just big enough so that he could see to walk. The box protected the adjustment of the device from the near constant Kansas wind. I can still see him in my mind’s eye walking across campus. He was a sight.

The point of his experiment was to try to create a partial blind spot in his vision by interfering with how light went through the pupil to the retina. And it worked. He reported to us that, right in the middle of his vision, he could not see. Not totally blind, just a blind spot. And thank goodness, only temporary.

I’m sure I don’t remember the experiment accurately, but I swear, as Dave Barry says, I am not making this up. And I find it an apt metaphor for our condition. We have a kind of self-imposed blindness. We’ve come tacitly to “know” that the immanent frame is all there is. Yes, people have what they may regard as transcendent experiences of beauty and mystery, but we can understand these things to our satisfaction with tools that we have created. In terms of how we experience life, the transcendent has collapsed into the immanent. In the final analysis, Isaiah’s experience is Isaiah’s experience. That’s all.

But of course, that isn’t all. Much more is needed to help us make sense of that feeling of and hunger for transcendence, that doesn’t and won’t go away, and, in our quiet moments, we know it. To our great blessing and, indeed, our salvation, the Unseen has become seen. “No one has ever seen God. It is God the only Son, who is close to the Father’s heart [literally, in the Father’s bosom], who has made him known.” The Unseen is seen, known. Not just a category of human experience that we call religious or spiritual, but God. The real, one, true, God.

We need healing, not just a vaccination. We need our sight to be restored, so that we can see more of the Unseen. God is not coy, playing hard to get. On the contrary, we have trained ourselves right into blindness. As we turn the corner on a miserable 2020 and look forward to a fresh calendar, my prayer is that, through scriptural therapy, we gain sight. We see the Unseen. May the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ enlighten us. And may that light shine through us to others.